Basic geology, paleontology, and fieldwork

Geologic exploration and observation in Kansas spans centuries, from Francisco Vasquez de Coronado's ill-fated search for gold in 1541 to Lewis and Clark's expedition in 1804 to the current research endeavors of the Kansas Geological Survey and other institutions. By 1889, when the Kansas Geological Survey was permanently established at the University of Kansas, the extraction and use of the state's natural resources were already underway and the discovery of large vertebrate marine fossils in western Kansas had ushered in a new age of paleontology nationally.

Early geologists, paleontologists, and other enthusiasts in Kansas depended on horses and horse-drawn wagons to reach remote natural treasures and to carry their food, shelter, surveying equipment, and other tools. Today's scientists have the advantage of modern transportation, GPS, computers, advances in chemical analysis, and in places, fortuitous access to previously deeply buried rocks and fossils exposed in quarries and in road cuts created to make highways smoother and travel less hazardous. Over the years, however, the simple rock hammer has remained one of the most essential tools for geologists and paleontologists.

Natural resource discovery and use prior to the mid-1800s in what is now Kansas was often happenstance. Exposed coal was reportedly gathered from hillsides around Fort Leavenworth in the 1820s. A Baptist missionary wrote of coal and salt springs along the Neosho River in eastern Kansas in 1828. Early military expedition and government survey reports did start to note resources of economic interest, from water and building stone to coal and valuable minerals. Not until after 1850, however, did scientists begin serious geologic reconnaissance, making note of the location, type, fossil content, and stratification (layering and sequence) of rocks.

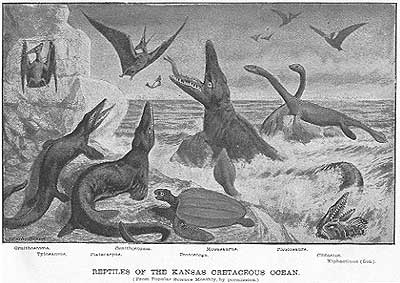

At first, studies were focused on eastern Kansas, where layers of limestones and other rocks—sometimes filled with marine fossils—provided evidence of seas that rose and fell during the Permian and Pennsylvanian periods. After railroads came through following the Civil War, scientists moved to western Kansas, were Cretaceous-age fossils of giant marine reptiles and fish, in particular, captured the country's imagination.

When an Army physician named Theophilus Turner, stationed at Fort Wallace in Wallace County, discovered the well-preserved bones of a large marine reptile known as a plesiosaur in 1868 he piqued the interest of famous paleontologists from as far away as the east coast. Among the fascinating finds between 1865 and 1895 were previously unreported species of reptiles and fishes, fossilized mosasaur skin, several new species of giant gliding reptiles known as pterosaurs, and a swimming bird, Ichthyornis, which was especially notable because the specimen found in Kansas was the first bird with teeth ever discovered.

Upon its founding, the Kansas Geological Survey was given the mission to make "a complete geological survey of the state of Kansas, giving special attention to any and all natural products of economic importance." Since then, hundreds of scientists have spent countless hours collecting, identifying, analyzing, and amassing information about rocks, fossils, and other natural resources on and below ground. Much is known and has been made readily available through publications and other resources for decision-makers, landowners, businesses, scientists, students, educators, and the general public. Yet much remains for future scientists to dig up, dig out, analyze, and explain.

Resources

Thof's Dragon and the Letters of Capt. Theophilus J. Turner, M.D., U.S. Army: Kansas History, 1987, v. 10, no. 3.

"To Bring Together, Correlate, and Preserve"—A History of the Kansas Geological Survey, 1864-1989: Kansas Geological Survey Bulletin 227.